Introduction

Freedom from colonial rule came with a price. The partition of India involved dividing the provinces of Bengal and Punjab into two. Though not envisaged at the time of the division, it was followed by migration of Hindus from East Bengal to West Bengal and Muslims from Bihar and West Bengal to East Bengal. Similarly, Hindus and Sikhs in West Punjab had to migrate to eastern Punjab and Muslims in eastern Punjab to western Punjab. The boundaries between India and Pakistan were to be determined on the composition of the people in each village on their religion; and villages where the majority were Muslims were to constitute Pakistan and where the Hindus were the majority to form India. There were other factors too: rivers, roads and mountains acted as markers of boundaries. The proposal was that the religious minorities – whether Hindus or Muslims – in these villages were to stay on and live as Indians (in case of Muslims) and Pakistanis (in case of Hindus) wherever they were. There was a separate scheme for those villages where the Muslims were a majority and yet the village not contiguous with the proposed territory of Pakistan and those villages where the Hindus were a majority and yet not contiguous with the proposed territory of India: they were to remain part of the nation with which the village was contiguous. A new complication had arisen by this time and that was the recognition of Sikhs as a religious identity in Punjab, in addition to the Hindus, and the Muslims; the Akali Dal had declared its preference to stay on with India irrespective of its people living in villages that would otherwise become part of Pakistan.

This complex situation was the consequence of the fast pace of developments in Britain on the issue of independence to India. The declaration on February 20, 1947 by Prime Minister Atlee, setting June 30, 1948 for the British to withdraw from India and Mountbatten’s arrival as viceroy replacing Wavell on March 22, 1947 had set the stage for the transfer of power to Indians. This was when the Muslim League leadership had gathered the support of a vast majority of the Muslim community behind it and disputing the claims of the Congress to represent all Indians. On June 3, 1947, Mountbatten advanced the date of British withdrawal to August 15, 1947. As for the communal question and the issue of two nations, the proposal was to hand over power to two successor dominion governments of India and Pakistan. The division of Bengal and the Punjab, as proposed, meant partition – a reality to which Congress finally reconciled. The Mountbatten plan for independence along with partition of India was accepted at the AICC meeting at Meerut on June 14, 1947.

Gandhi, who had opposed the idea of division with vehemence in the past, now conceded its inevitability. Gandhi explained the change. He held that the unabated communal violence and the participation in it of the people across the Punjab and in Bengal had left himself and the Congress with no any strength to resist partition. Sadly, the canker of communalism and the partition system that the colonial collaborators produced took its toll on the infant Indian nation. It began with the assassination of the Mahatma on January 30, 1948. How did the infant nation take up the challenge, resolving some and grappling with some others in the years to come?

Jawaharlal Nehru put this aptly in his address to the members of the Constituent Assembly in the intervening night on August 14/15, 1947, in which he laid out the roadmap, its ideals and the inevitability of taking such a path. “Long years ago we made a tryst with destiny, and now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially….” Teachers may put on screen the full speech by Jawaharlal Nehru and share the experience of listening to it with the class: Speech may be accessed from https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=Uj4TfcELODM

Consequences of Partition

The challenges before free India included grappling with the consequences of partition, planning the economy and reforming the education system (which will be dealt with in the following lesson), making a Constitution that reflected the aspirations kindled by the freedom struggle, merger of the Princely states (more than 500 in number and of different sizes), and resolving the diversity on the basis of languages spoken by the people with the needs of a nation-state. Further, a foreign policy that was in tune with the ideals of democracy, sovereignty and fraternity had to be formulated.

The partition of India on Hindu–Muslim lines was put forth as a demand by the Muslim League in vague terms ever since its Lahore session (March 1940). But its architecture and execution began only with Lord Mountbatten’s announcement of his plan on June 3, 1947 and advancing the date of transfer of power to August 15, 1947. The time left between the two dates was a mere 72 days.

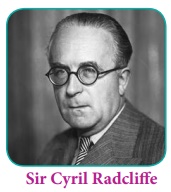

Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a lawyer by training with no exposure to India and its reality, was sent from London to re-draw the map of India. Its execution was left to the dominion governments of India and Pakistan after August 15, 1947.

Radcliffe arrived in India on July 8, 1947.He was given charge of presiding over two Boundary Commissions: one for the Punjab and the other for Bengal.Two judges from the Muslim community and two from the Hindu community were included. The commissions were left with five weeks to identify villages as Hindu or Muslim majority on the basis of the 1941 census. It is widely accepted that the census of 1941, conducted in the midst of the World War II led to faulty results everywhere.

The commissions were also constrained by factors such as contiguity of villages and by demands of the Sikh community that villages in West Punjab where their shrines were located be taken into India irrespective of the population of Sikhs in those villages. The two commissions submitted the report on August 9, 1947. Mountbatten’s dispensation, meanwhile, decided to postpone the execution of the boundaries to a date after power was transferred to the two dominions. The contours of the two dominions – India and Pakistan – were drawn in the scheme on August 14/15, 1947 insofar as the administration was concerned; the people, however, were not informed about the new map when they celebrated independence day on August 14/15, 1947.

Radcliffe’s award contained all kinds of anomalies. The provincial assembly in Punjab had resolved that West Punjab would go to Pakistan. The other provinces, which were geographically contiguous with Pakistan such as Sind, Baluchistan and the North-West Frontier Provinces followed this. Similarly, the Bengal Assembly, resolved that the eastern parts of the province were to constitute Pakistan on this side.

The award Radcliffe presented, on August 9, 1947, marked 62,000 square miles of land that was hitherto part of the Punjab to Pakistan. The total population (based on the 1941 census) of this region was 15,800,000 people of whom 11,850,000 were Muslims. Almost a quarter of the population in this territory – West Punjab – were non-Muslims; and the Mountbatten Plan as executed by Sir Radcliffe meant they continued to live as minorities in Pakistan. Similarly, East Punjab that was to be part of India was demarcated to consist of 37,000 square miles of territory with a population of 12,600,000. Of this, 4,375,000 were Muslims. In other words, more than a third of the population in east Punjab would be Muslims.

The demographic composition of the Indian and Pakistani parts of Bengal was no less complicated. West Bengal that remained part of India accounted for an area of 28,000 square miles with a population of 21,200,00 out of which 5,30,000 were Muslims; in other words, Muslims constituted a quarter of the population of the Indian part of the former Bengal province. Sir Radcliffe’s commission marked 49,400 square miles of territory from former Bengal with 39,100,000 people for Pakistan. The Muslim population there, according to the 1941 census, was 27,700,000. In other words, 29 per cent of the population were Hindus. East Pakistan (which became Bangladesh in December 1971) was constituted by putting together the eastern part of divided Bengal, Sylhet district of Assam, the district of Khulna in the region and also the Chittagong Hill tracts. Such districts of Bengal as Murshidabad, Malda and Nadia which had a substantially large Muslim population were left to remain in India. The exercise was one without a method.

The re-drawn map of India was left with the two independent governments by the colonial rulers. It was left to the independent governments of India and Pakistan to fix the exact boundaries. However, the understanding was that the religious minorities in both the nations – the Hindus in West and East Pakistan and the Muslims in India, in East Punjab and West Bengal as well as in United Provinces and elsewhere – would continue to live as minorities but as citizens in their nations.

After the partition, there were as many as 42 million Muslims in India and 20 million non-Muslims (Hindus, Sindhis and Sikhs) in Pakistan. The vivisection of India, taking place as it did in the middle of heightened Hindu-Muslim violence, had rendered a smooth transition impossible. Despite the conspicuous exhibition of Hindu–Muslim unity during the RIN mutiny and the INA trials (see previous lesson), the polity now resembled a volcano. Communal riots had become normal in many parts of India, and were most pronounced in the Punjab and Bengal. Minorities on both sides of the divide lived in fear and insecurity even as the two nations were born. That Gandhi, who led the struggle for freedom from the front and whom the colonial rulers found impossible to ignore, stayed far away from New Delhi and observed a fast on August 15, 1947, was symbolic. The partition brought about a system in place where the minorities on either side were beginning to think of relocating to the other side due to fear and insecurity.

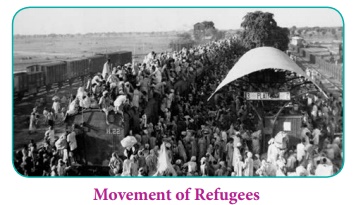

As violence spread, police remained mute spectators. This triggered more migration of the minorities from both nations. In the four months between August and November 1947, as many as four-and-a-half million people left West Pakistan to India, reaching towns in East Punjab or Delhi. Meanwhile, five-and-a-half million Muslims left their homes in India (East Punjab, United Provinces and Delhi) to live in Pakistan. A large number of those who left their homes on either side of the newly marked border thought they would return after things normalised; but that was not to be. Similar migration happened between either sides of the new border in Bengal too.

Partition: A Poem by W.H.Auden

Unbiased at least he was when he arrived on his mission,

Having never set eyes on the land he was called to partition

Between two peoples fanatically at odds,

With their different diets and incompatible gods.

‘Time,’ they had briefed him in London, ‘is short. It’s too late

For mutual reconciliation or rational debate:

The only solution now lies in separation.

The Viceroy thinks, as you will see from his letter,

That the less you are seen in his company the better,

So we’ve arranged to provide you with other accommodation.

We can give you four judges, two Moslem and two Hindu,

To consult with, but the final decision must rest with you.’

Shut up in a lonely mansion, with police night and day

Patrolling the gardens to keep the assassins away,

He got down to work, to the task of settling the fate Of millions.

The maps at his disposal were out of date

And the Census Returns almost certainly incorrect,

But there was no time to check them, no time to inspect Contested areas.

The weather was frightfully hot,

And a bout of dysentery kept him constantly on the trot,

But in seven weeks it was done, the frontiers decided,

A continent for better or worse divided.

The next day he sailed for England, where he could quickly forget

The case, as a good lawyer must. Return he would not,

Afraid, as he told his Club, that he might get shot.

Historian Gyanendra Pandey records 500,000 non-Muslim (Hindus and Sikhs) refugees flowing into the Punjab and Delhi in 1947-48. Pandey also records that several thousand Muslims were forced out of their homes in Delhi and nearby places by violent mobs to seek asylum in camps set up around the Red Fort and the Purana Quila. Refugee camps were set up but they had hardly any sanitation and water supply.

In both countries property left behind by the fleeing families were up for grabs. The long line of refugees walking crossing the borders was called ‘kafila’. The refugees on the march were targets for gangs belonging to the ‘other’ community to wreak vengeance. Trains from either side of the new border in the Punjab were targeted by killer mobs and many of those reached their destination with piles of dead bodies. The violence was of such a scale that those killed the numbers of remains mere estimates. The number ranges between 200,000 to 500,000 people dead and 15 million people displaced.

Even as late as in April 1950, the political leadership of the two nations wished and hoped to restore normality and the return of those who left their homes on either side. On April 8, 1950, Nehru and Liaquat Ali Khan signed the Delhi pact, with a view to restoring confidence among the minorities on both sides. This, however, failed to change the ground reality. Even while the pact was signed the Government of India was also working on measures to rehabilitate those who had left West Punjab to the East and to Delhi and render them vocational skills and training. The wounds caused by the partition violence hardly healed even after decades. Scores of literary works stand testimony to the trauma of partition.

The partition posed a bigger challenge before Nehru and the Constituent Assembly, now engaged with drafting the founding and the fundamental law of the nation: to draft a constitution that is secular, democratic and republican as against Pakistan’s decision to become an Islamic Republic.

Making of the Constitution

It was a demand from the Indian National Congress, voiced formally in 1934, that the Indian people shall draft their constitution rather than the British Parliament. The Congress thus rejected the White Paper circulated by the colonial government. The founding principle that Indians shall make their own constitution was laid down by Gandhi as early as in 1922. Gandhi had held that rather than a gift of the British Parliament, swaraj must spring from ‘the wishes of the people of India as expressed through their freely chosen representatives’.

Elections were held, based on the 1935 Act, to the Provincial Assemblies in August 1946. These elected assemblies in turn were to elect the Central Assembly, which would also become the Constituent Assembly. The voters in the July 1946 elections to the provinces were

those who owned property – the principle of universal adult franchise was still a far cry. The results revealed the Muslim League’s command in Muslim majority constituencies while the Indian National Congress swept the elections elsewhere. The League decided to stay away from the Constitution making process and pressed hard for a separate nation. The Congress went for the Constituent assembly.

The elected members of the various Provincial assemblies voted nominees of the Congress to the Constituent Assembly. The Constituent Assembly (224 seats) that came into being, though dominated by the Congress, also included smaller outfits such as the communists, socialists and others. The Congress ensured the election of Dr B.R. Ambedkar from a seat in Bombay and subsequently elected him chairman of the drafting committee. Apart from electing its own stalwarts to the Assembly, the Congress leadership made it a point to send leading constitutional lawyers.

This was to make a constitution that contained the idealism that marked the freedom struggle and the meaning of swaraj, as specified in the Fundamental Rights Resolution passed by the Indian National Congress at its Karachi session (March 1931). This, indeed, laid the basis for the making of our constitution a document conveying an article of faith guaranteeing to the citizens a set of fundamental rights as much as a set of directive principles of state policy. The constitution also committed the nation to the principle of universal adult franchise, and an autonomous election commission. The constitution also underscored the independence of the judiciary as much as it laid down sovereign law-making powers with the representatives of the people.

The members of the constituent assembly were not averse to learn and pick up features from the constitutions from all over the world; and at the same time they were clear that the exercise was not about copying provisions from the various constitutions from across the world.

Jawaharlal Nehru set the ball rolling, on December 13, 1946, by placing the Objectives Resolution before the Constituent Assembly. The assembly was convened for the first time, on December 9, 1946. Rajendra Prasad was elected chairman of the House. The Objectives Resolution is indeed the most concise introduction to the spirit and the contents

The Objectives Resolution is indeed the most concise introduction to the spirit and the contents of the Constitution of India. The importance of this resolution can be understood if we see the Preamble to the Constitution and the Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles of State Policy enshrined in it and as adopted on November 26, 1949.

The Constitution of India, thus, marked a new beginning and yet established continuity with India’s past. The Fundamental Rights drew everything from clause 5 of the Objectives Resolution as much as from the rights enlisted by the Indian National Congress at its Karachi session (discussed in Lesson 5). The spirit of the Constitution was drawn from the experience of the struggle for freedom and the legal language from the Objectives Resolution and most importantly from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), promulgated by the United Nations on December 10, 1948.

Merger of Princely States

The adoption of the Constitution on November 26, 1949 was only the beginning of a bold new experiment by the infant nation. There were a host of other challenges that the nation and its leaders faced and they had to be addressed even while the Constituent Assembly met and started its job of drafting independent India’s constitution. Among them was the integration of the Indian States or the Princely States.

The task of integrating the Princely States into the Indian Union was achieved with such speed that by August 15, 1947, except Kashmir, Junagadh and Hyderabad, all had agreed to sign an Instrument of Accession with India, acknowledging its central authority over Defence, External Affairs and Communications.

The task of integrating these states, with one or the other Provinces of the Indian Union was accomplished with ease. The resolution passed at the All India States People’s Conference (December 1945 and April 1947) that states refusing to join the Constituent Assembly would be treated as hostile was enough to get the rulers to sign the Instrument of Accession in most cases. There was the offer of a generous privy purse to the princes. The rapid unification of India was ably handled and achieved by Sardar Home Minister in the Interim Cabinet was also entrusted with the States Ministry for this purpose. The People’s Movements exerted pressure on the princes to accede to the Indian union.

The long, militant struggle that went on in the Travancore State for Responsible Government culminating in the Punnapra–Vayalar armed struggle against the Diwan, Sir C.P. Ramaswamy, the Praja Mandal as well as some tribal agitations that took place in the Orissa region – Nilagiri, Dhenkanal and Talcher – and the movement against the Maharaja of Mysore conducted by the Indian National Congress all played a major role in the integration of Princely States.

Yet, there was the problem posed by the recalcitrant ruler of Hyderabad, with the Nizam declaring his kingdom as independent. The ruler of Junagadh wanted to join Pakistan, much against the wishes of the people. Similarly, the Hindu ruler of Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, declared that Kashmir would remain independent while the people of the State under the leadership of the National Conference had waged a “Quit Kashmir” agitation against the Maharaja. It must be stressed here that the movement in Kashmir as well as the other Princely States were also against the decadent practice of feudal land and social relations that prevailed there.

“The police action” executed in Hyderabad within 48 hours after the Nizam declared his intentions demonstrated that India meant business. It was the popular anger against the Nizam and his militia, known as the Razakkars, that was manifest in the Telengana people’s movement led by the communists there which provided the legitimacy to “the police action”.

Though Patel had been negotiating with the Maharaja of Kashmir since 1946, Hari Singh was opposed to accession. However, in a few months after independence – in October 1947 – marauders from Pakistan raided Kashmir and there was no way that Maharaja Hari Singh could resist this attack on his own. Before India went to his rescue the Instrument of Accession was signed by him at the instance of Patel. Thus Kashmir too became an integral part of the Indian Union.

This process and the commitment of the leaders of independent India to the concerns of the people of Kashmir led the Constituent Assembly to provide for autonomous status to the State of Jammu and Kashmir under Article 370 of the Constitution.

Instrument of Accession: A legal document, introduced in Government of India Act, 1935, which was later used in the context of Partition enabling Indian rulers to accede their state to either India or Pakistan.

Linguistic Reorganization of States

An important aspect of the making of independent India was the reorganisation of states on linguistic basis. The colonial rulers had rendered the sub-continent into administrative units, dividing the land by way of Presidencies or Provinces without taking into account the language and its impact on culture on a region. Independence and the idea of a constitutional democracy meant that the people were sovereign and that India was a multi-cultural nation where federal principles were to be adopted in a holistic sense and not just as an administrative strategy.

The linguistic reorganization of states was raised and argued out in Constituent Assembly between 1947 and 1949. The assembly however decided to hold it in abeyance for a while. This was on the grounds that the task was huge and could create problems in the aftermath of the partition and the accompanying violence.

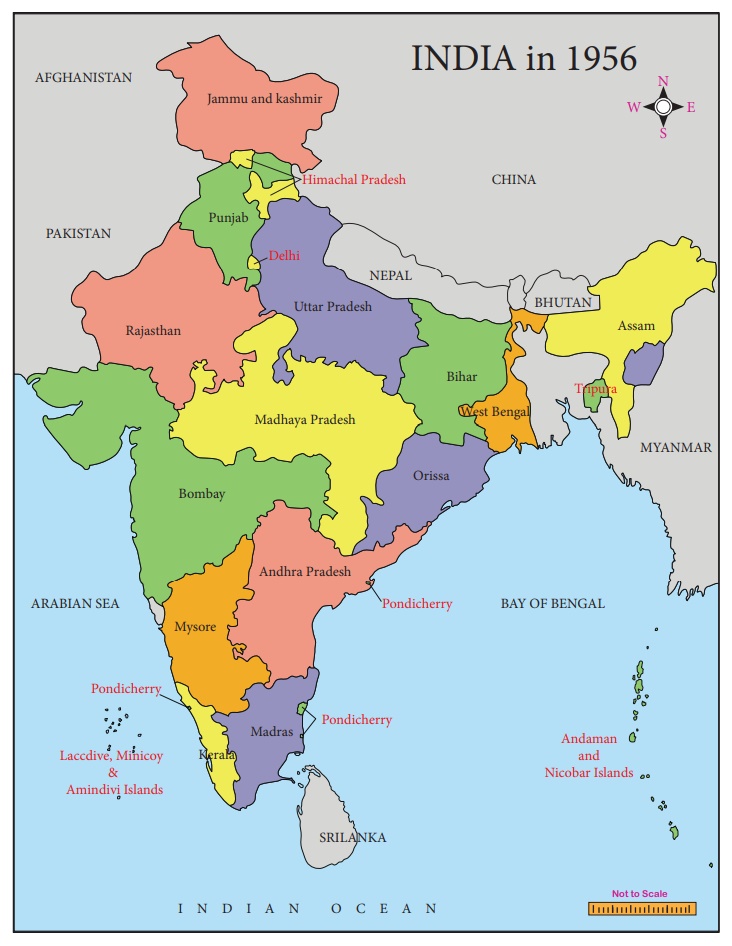

After the Constitution came into force it began to be implemented in stages, beginning with the formation of a composite Andhra Pradesh in 1956. It culminated in the trifurcation of Punjab to constitute a Punjabi-speaking state of Punjab and carving out Haryana and Himachal Pradesh from the existing state of Punjab in 1966.

The idea of linguistic reorganisation of states was integral to the national movement, at least since 1920. The Indian National Congress, at its Nagpur session (1920), recorded that the national identity will have to be necessarily achieved through linguistic identity and resolved to set up the Provincial Congress Committees on a linguistic basis. It took concrete expression in the Nehru Committee Report of 1928. Section 86 of the Nehru Report read: “The redistribution of provinces should take place on a linguistic basis on the demand of the majority of the population of the area concerned, subject to financial and administrative considerations.”

This idea was expressed, in categorical terms, in the manifesto of the Indian National Congress for the elections to the Central and Provincial Legislative Assemblies in 1945. The manifesto made a clear reference to the reorganisation of the provinces: “… it (the Congress) has also stood for the freedom of each group and territorial area within the nation to develop its own life and culture within the larger framework, and it has stated that for this purpose such territorial areas or provinces should be constituted as far as possible, on a linguistic and cultural basis…”

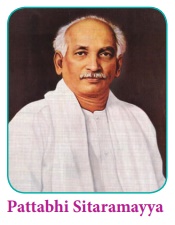

On August 31, 1946, only a month after the elections to the Constituent Assembly, Pattabhi Sitaramayya raised the demand for an Andhra Province: “The whole problem” he wrote, “must be taken up as the first and foremost problem to be solved by the Constituent Assembly”. He also presided over a conference, on December 8, 1946, that passed a resolution demanding that the Constituent Assembly accept the principle for linguistic reorganisation of States. The Government of India in a communique stated that Andhra could be mentioned as a separate unit in the new Constitution as was done in case of the Sind and Orissa under the Government of India Act, 1935.

The Drafting Committee of the Constituent Assembly, however, found such a mention of Andhra was not possible until the geographical schedule of the province was outlined. Hence, on June 17, 1948, Chairman Rajendra Prasad set up a 3-member commission, called The Linguistic Provinces Commission with a specific brief to examine and report on the formation of new provinces of Andhra, Kerala, Karnataka and Maharashtra. Its report, submitted on December 10, 1948, listed out reasons against the idea of linguistic reorganisation in the given context. It dealt with each of the four proposed States – Andhra, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra – and concluded against such an idea.

However, the demand for linguistic reorganisation of states did not stop. The issue gained centre-stage with Pattabhi Sitaramayya’s election as the Congress President at the Jaipur session. A resolution there led to the constitution of a committee with Sardar Vallabhai Patel, Pattabhi Sitaramayya and Jawaharlal Nehru (also called the JVP committee).

The JVP committee submitted its report on April 1, 1949. It too held that the demand for linguistic states, in the given context, as “narrow provincialism’’ and that it could become a menace’’ to the development of the country. The JVP committee also held out that “while language is a binding force, it is also a separating one’’. However, it stressed that it was possible that “when conditions are more static and the state of peoples’ minds calmer, the adjustment of these boundaries or the creation of new provinces can be undertaken with relative ease and with advantage to all concerned.’’

The committee said in conclusion that it was not the right time to embark upon the idea of linguistic reorganisation of States. In other words, the consensus was that the linguistic reorganisation of states be postponed. There was provision for re-working the boundaries between states and also for the formation of new states from parts of existing states. The makers of the Constitution did not qualify the reorganisation of the States as only on linguistic basis but left it open as long as there was agreement on such reorganisation.

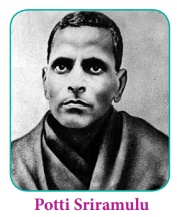

The idea of linguistic states revived soon after the first general elections were over. Potti Sriramulu’s fast demanding a separate state of Andhra, beginning October 19, 1952 and his death thereafter on December 15, 1952.

Article 3, reads as follows:

Parliament may by law- (a) form a new State by separation of territory from any State or by uniting two of more States or parts of States by uniting any territory to a part of any State; (b) increase the area of any State; (c) diminish the area of any State; (d) alter the boundaries of any State;

This led to the constitution of the States Reorganisation Commission, with Fazli Ali as Chairperson, and K.M. Panikkar and H.N. Kunzru as members. The Commission submitted its report in October 1955. The Commission recommended the following States to constitute the Indian Union: Madras, Kerala, Karnataka, Hyderabad, Andhra, Bombay, Vidharbha, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, Assam, Orissa and Jammu & Kashmir. In other words, the Commission’s recommendations were a compromise between administrative convenience and linguistic concerns.

The Nehru regime, however, was, by then, committed to the principle of linguistic reorganization of the States and thus went ahead implementing the States Reorganisation Act, 1956. Andhra Pradesh, including the Hyderabad State came into existence. Kerala, including the Travancore-Cochin State and the Malabar district of Madras, came into existence. Karnataka came into being including the Mysore State and also parts of Bombay and Madras States. In all these cases, the core principle was linguistic identity.

In May 1960 Gujarat was created from Maharastra to fulfil the demand of the Gujarati speaking people. Subsequently, the demand for a Punjabi subha continued to be described by the establishment as separatist until 1966. The trifurcation of Punjab, brought to an end the process that was initiated by the Indian National Congress, in 1920, to put language as the basis for the reorganization of the provinces.

India’s Foreign Policy

The founding principles of independent India’s foreign policy were, in fact, formulated at least three decades before independence. It evolved in the course of the freedom struggle and was rooted in its conviction against any form of colonialism. Jawaharlal Nehru was its prime architect.

India’s foreign policy was based on certain basic principles. They are: anti-colonialism, anti-imperialism, anti-apartheid or anti-racism, non-alignment with the super powers, Afro-Asian Unity, non-aggression, non-interference in other’s internal affairs, mutual respect for each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, and the promotion of world peace and security. The commitment to peace between nations was not placed in a vacuum; it was placed with an equally emphatic commitment to justice.

The context in which India’s foreign policy was formulated was further complicated by the two contesting power blocs that dominated the world in the post-war scenario: the US and the USSR. Independent India responded to this with non-alignment as its foreign policy doctrine.

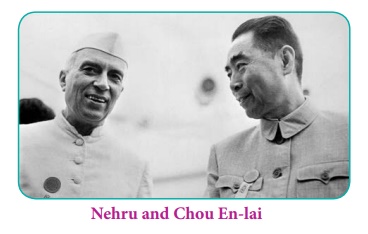

Before we go into the details of non-alignment, it will be useful to look at India’s relationship with China since independence. China was liberated by its people from Japanese colonial expansionism in 1949, just two years after India’s Independence. Nehru laid a lot of importance on friendship with China, with whom India shared a long border.

India was the first to recognize the new People’s Republic of China on January 1, 1950. The shared experience of suffering at the hands of colonial powers and its consequences –poverty and underdevelopment – in Nehru’s perception was force enough to get the two nations to join hands to give Asia its due place in the world. Nehru pressed for representation for Communist China in the UN Security Council. However, when China occupied Tibet, in 1950, India was unhappy that it had not been taken into confidence. In 1954, India and China signed a treaty in which India recognized China’s rights over Tibet and the two countries placed their relationship within a set of principles, widely known since then as the principles of Panch Sheel.

Panch Sheel (five virtues)

1. Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty

2. Mutual non-aggression

3. Mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs

4. Equality and cooperation for mutual benefit

5. Peaceful co-existence

Meanwhile, Nehru took special efforts to project China and Chou En-lai at the Bandung Conference, held in April 1955. In 1959, the Dalai Lama, fled Tibet along with thousands of refugees after a revolt by the Buddhists was crushed by the Chinese government. The Dalai Lama was given asylum in India and it made the Chinese unhappy. Soon after, in October 1959, the Chinese opened fire on an Indian patrol near the Kongka pass in Ladakh, killing five Indian policemen and capturing a dozen others. Though talks were held at various levels including with Chou En-lai, not much headway was made.

Then came the 1962 war with China. On 8 September 1962, Chinese forces attacked the Thagla ridge and dislodged Indian troops. All the goodwill and attempts to forge an Asian bloc in the world came to a stop. India took a long time to recover from the blow to its self-respect, and perhaps it was only the victory over Pakistan in the Bangladesh war, in which China and the US were also supporting Pakistan, that restored the sense of self-worth.

India’s contribution to the world, however, was not restricted to its relationship with China and the Panch Sheel. It was most pronounced and lasting in the form of non-alignment and its concretisation at the Bandung Conference.

In March 1947, Nehru organised the Asian Relations Conference, attended by more than twenty countries. The theme of the conference was Asian independence and assertion on the world stage. Another such conference was held in December 1948 in specific response to the Dutch attempt to re-colonize Indonesia. The de-colonization initiative was carried forward further at the Asian leaders’ conference in Colombo in 1954, culminating in the Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955. The Bandung Conference set the stage for the meeting of nations at Belgrade and the birth of the Non-Aligned Movement.

The architect of independent India’s foreign policy, indeed, was Jawaharlal Nehru and the high point of it was reached in 1961 when he stood with Nasser of Egypt and Tito of Yugoslavia to call for nuclear disarmament and peace. The importance of non-alignment and its essence in such a world is best explained from what Nehru had to say about it.

“So far as all these evil forces of fascism, colonialism and racialism or the nuclear bomb and aggression and suppression are concerned, we stand most emphatically and unequivocally committed against them . . . We are unaligned only in relation to the cold war with its military pacts. We object to all this business of forcing the new nations of Asia and Africa into their cold war machine. Otherwise, we are free to condemn any development which we consider wrong or harmful to the world or ourselves and we use that freedom every time the occasion arises.”

Bandung Declaration

A 10-point “declaration on promotion of world peace and cooperation,” incorporating the principles of the United Nations Charter was adopted unanimously:

1. Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the charter of the United Nations

2. Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations

3. Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small

4. Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country

5. Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself, singly or collectively, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

6. (a) Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defence to serve any particular interests of the big powers

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries

7. Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country

8. Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties own choice, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

9. Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation

10. Respect for justice and international obligations.