Introduction

The political and economic centralisation of India achieved by the British for the better exploitation and control of India inevitably led to the growth of national consciousness and the birth of the national movement. The history of nationalism in India begins with the campaigns and struggles for social reforms in the nineteenth century followed by the Western-educated Indians’ prayers and petitions for political liberties. With the return of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi from South Africa in 1915, and his leadership of the Indian nationalist movement in 1919 Indian nationalism entered a mass phase.

Nationalism: Broadly, nationalism meansloyalty and devotion to a nation. It is a consciousness or tendency to exalt and place one nation above all others, emphasising promotion of its culture and interests as opposed to those of other nations.

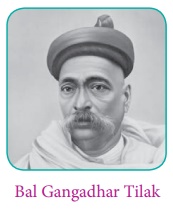

Prior to Gandhi, prominent leaders like Dadabhai Naoroji, Gopal Krishna Gokhale, Bipin Chandra Pal, Lala Lajpat Rai, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, and others took the early initiative to educate the Indians about their national identity and colonial exploitation. In this chapter, while tracing the origin and growth of Indian Nationalism, we focus on the contribution of these leaders who are known as the early nationalists.

Socio-economic Background

(a) Implications of the New Land Tenures

The British destroyed the traditional basis of Indian land system. In the pre-British days, the land revenue was realised by sharing the actual crop with the cultivators. The British fixed the land revenue in cash without any regard to various contingencies, such as failure of crops, fall in prices and droughts or floods. Moreover, the practice of sale in settlement of debt encouraged money lenders to advance money to landholders and resorting to every kind of trickery to rob them of their property.

There were also two other major implications of the new land settlements introduced by the East India Company. They institutionalised the commodification of land and commercialisation of agriculture in India. As mentioned earlier, there was no private property in land in pre-British era. Now, land became a commodity that could be transferred either by way of buying and selling or by way of the administration taking over land from holders, in lieu of default on payment of tax/rent. Land taken over in such cases was auctioned off to another bidder. This created a new class of absentee landlords who lived in the cities and extracted revenue from the lands without actually living on the lands. In the traditional agricultural set-up, the villagers produced largely for their consumption among themselves. After the new land settlements, agricultural produce was predominantly for the market.

The commodification of land and commercialisation of agriculture did not improve the lives and conditions of the peasants. Instead, this created discontent among the peasantry and made them restive. These peasants later on turned against the imperialists and their collaborators.

(b) Laissez Faire Policy and De-industrialization: Impact on Indian Artisans

The policy of the Company in the wake of Industrial Revolution in England resulted in the de-industrialization of India. This continued until the beginning of the World War I. The British Government pursued a policy of free trade or laissez faire. Raw materials like cotton, jute and silks from India were taken to Britain.

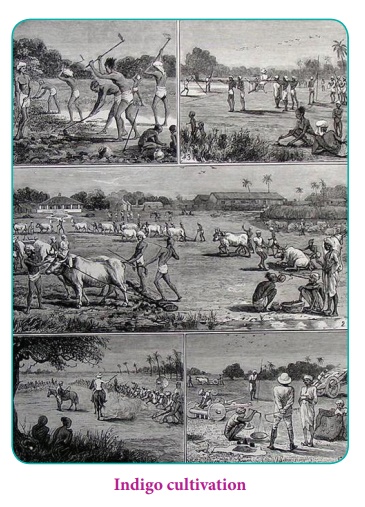

The finished products made from those raw materials were then transported back to the Indian markets. Mass production with the help of technological advancement enabled them to flood the Indian market with their goods. It was available at a comparatively cheaper price than the Indian handloom cloth. Prior to the arrival of the British, India was known for its handloom products and handicrafts. It commanded a good world market. However, as a result of the colonial policy, gradually Indian handloom products and handicrafts lost there market, domestic as well as international. Import of English articles into India threw the weavers, the cotton dressers, the carpenters, the blacksmiths and the shoemakers out of employment. India became a procurement area for the raw material and the farmers were forced to produce industrial crops like indigo and other cash crops like cotton for use in British factories. Due to this shift, subsistence agriculture, which was the mainstay for several hundred years, suffered leading to food scarcity.

The Indigo revolt of 1859 – 60 in Bengal was one of the responses from the Indian farmer to the oppressive policy of the British. Indian tenants were forced to grow indigo by their planters who were mostly Europeans. Used to dye the clothes indigo was in high demand in Europe. Peasants were forced to accept meagre amounts as advance and enter into unfair contracts. Once a peasant accepted the contract, he had no option but to grow indigo on his land. The price paid by the planter was far lower than the market price. Many a times, the peasants could not even pay their land revenue dues. Hoping that the authorities would address their concerns, the peasants wrote several petitions to authorities and organised peaceful protests. As their plea for reform went in vain, they revolted by refusing to accept any further advances and enter into new contracts. Peasants, through the Indigo revolt of 1859-60, were able to force the planters to withdraw from northern-Bengal.

(c) Famines and Emigration of Indians to Overseas British Colonies

Famines

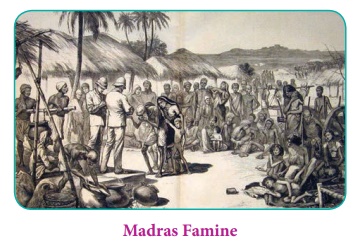

As India became increasingly de-industrialised and weavers and artisans engaged in handicrafts were thrown out of employment, there were recurrent famines due to the neglect of irrigation and oppressive taxation on land. Before the arrival of the British, Indian rulers had ameliorated the difficulties of the populace in times of famines by providing tax relief, regulating the grain prices and banning food exports from famine-hit areas. But the British extended their policy of non-intervention (laissez faire) even to famines. As a result, millions of people died of starvation during the Raj. It has been estimated that between 1770 and 1900, twenty five million Indians died in famines. William Digby, the editor of Madras Times, pointed out that during 1793-1900 alonean estimated five million people had died in all the wars around the world, whereas in just ten years (1891-1900), nineteen million had died in India in famines alone.

Sadly when people were dying of starvation millions of tonnes of wheat was exported to Britain. During the 1866 Orissa Famine, for instance, while a million and a half people starved to death, the British exported 200 million pounds of rice to Britain. The Orissa Famine prompted nationalist Dadabhai Naoroji to begin his lifelong investigations into Indian poverty. The failure of two successive monsoons caused a severe famine in the Madras Presidency during 1876-78. The viceroy Lytton adopted a hands-off approach similar to that followed in Orissa. An estimated 3.5 million people died in the Madras presidency.

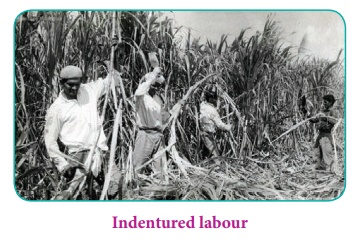

Indentured Labour

The introduction of plantation crops such as coffee, tea and sugar in Empire colonies such as Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Mauritius, Fiji, Malaya, the Caribbean islands, and South Africa required enormous labour. In 1815, the Governor of Madras received a communication from the Governor of Ceylon asking for “coolies” to work on the coffee plantations. The Madras Governor forwarded this letter to the collector of Thanjavur, who reported that the people were very much attached to the soil and unless some incentive was provided it was not easy to make them move out of their native soil. But the outbreak of two famines (1833 and 1843) forced the people, without any incentive from the government, to leave for Ceylon to work as coolies in coffee and tea plantations under the indentured labour system. The abolition of slavery in British India in 1843 also facilitated the processes of emigration to Empire colonies. In 1837 the number of immigrant Tamil labourers employed in Ceylon coffee estate was estimated at 10,000. The industry developed rapidly and so did the demand for Tamil labour. In 1846 its presence was estimated at 80,000 and in 1855 at 128,000 persons. In 1877, the famine year, there were nearly 380,000 Tamil labourers in Ceylon.

Besides Ceylon, many Indians opted to emigrate as indentured labour to other British colonies such as Mauritius, Straits Settlements, Caribbean islands, Trinidad, Fiji and South Africa. In 1843 it was officially reported that 30,218 male and 4,307 females had entered Mauritius as indentured labourers. By the end of the century some 5,00,000 labourers had moved from India to Mauritius.

Indentured Labour: Under this penal contractsystem (indenture), labourers were hired for a period of five years and they could return to their homeland with passage paid at the end. Many impoverished peasants and weavers went hoping to earn some money. It turned out to be as worse than slave labour. The colonial state allowed agents (kanganis) to trick or kidnap indigent landless labourers. The labourers suffered terribly on the long sea voyages and many died on the way. The percentage of deaths of indentured labour during 1856-57, in a ship bound for Trinidad from Kolkata is as follows: 12.3% of all males, 18.5% of the females, 28% of the boys 36% of the girls and 55% of the infants perished.

Western Education and its Impact

(a) Education in Pre-British India

Education in pre-colonial India was characterised by segmentation along religious and caste lines. Among the Hindus, Brahmins had the exclusive privilege to acquire higher religious and philosophical knowledge. They monopolised the education system and occupied positions in the society, primarily as priests and teachers. They studied in special seminaries such as Vidyalayas and Chatuspathis. The medium of instruction was Sanskrit, which was considered as the sacred language. Technical knowledge – especially in relation to architecture, metallurgy, etc. – was passed hereditarily. This came in the way of innovation. Another shortcoming of this system was that it barred women, lower castes and other under-privileged people from accessing education. The emphasis on rote learning was another impediment to innovation.

(b) Contribution of Colonial State: Macaulay System of Education

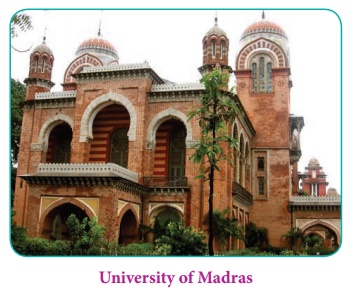

The colonial government aided the spread of modern education in India for a different reason than educating and empowering the Indians. To administer a large colony like India, the British needed a large number of personnel to work for them. It was impossible for the British to import the educated lot, needed in such large numbers, from Britain. With this aim, the English Education Act was passed by the Council of India in 1835. T.B. Macaulay drafted this system of education introduced in India. Consequently, the colonial administration started schools, colleges and universities, imparting English and modern education, in India. Universities were established in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta in 1857. The colonial government expected this section of educated Indians to be loyal to the British and act as the pillars of the British Raj.

T. B. Macaulay was India’s first law member of the Governor General in Council from 1834 to 1838. Before Macaulay arrived in India the General Committee of Public Instruction was formed in 1823 with the responsibility to guide the East India Company on the matter of education and the medium of instruction. The Committee was split into two groups. The Orientalist group advocated education in vernacular languages. The Anglicists advocated Western education in English.

Macaulay was on the side of Anglicists and wrote his famous ‘Minute on Indian Education’ in 1835. In this Minute, he argued for Western education in the English language. His intention behind supporting the Anglicists was that he wanted to create a class of persons from within India who would ‘be Indian in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals and in intellect’.

The British created an educated Indian middle class for their own ends but sneered at it as the Babu class. That very class, however, became the progressive intelligentsia of India and played a leading role in mobilising the people for the liberation of the country.

(c) Role of Educated Middle Class

The economic and administrative transformation on the one side and the growth of Western education on the other gave the space for the growth of new social classes. From within these social classes, a modern Indian intelligentsia emerged. The “neo-social classes” created by the British Raj, which included the Indian trading and business communities, landlords, money lenders, English-educated Indians employed in imperial subordinate services, lawyers and doctors, initially adopted a positive approach towards the colonial administration. However, soon they realised that their interests would be better served only in independent India. People of the said social classes began to play a prominent role in promoting patriotism amongst the people. The consciousness of these classes found articulation in a number of associations prior to the founding of the Indian National Congress at the national level.

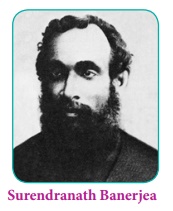

Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Swami Vivekananda, Aurobindo Ghose, Gopala Krishna Gokhale, Dadabhai Naoroji, Feroz Shah Mehta, Surendra Nath Banerjea and others who belonged to modern Indian intelligentsia led the social, religious and political movements in India. Educated Indians had exposure to ideas of nationalism, democracy, socialism, etc. articulated by John Locke, James Stuart Mill, Mazzini, Garibaldi, Rousseau, Thomas Paine, Marx and other western intellectuals. The right of a free press, the right of free speech and the right of association were the three inherent rights, which their European counterparts held dear to their heart, and the educated Indians too desired to cling to. Various forums came into existence, where people could meet and discuss the issues affecting their interests. This became possible now at the national level, due to the rapid expansion of transport network and establishment of postal, telegraph and wireless services all over India.

(d) Contribution of Missionaries

One of the earliest initiatives to impart modern education among Indians was taken up by the Christian missionaries. Inspired by the proselytizing sprit, they attacked polytheism and caste inequalities that were prevalent among the Hindus. One of the methods adopted by the missionaries, to preach Christianity, was through modern secular education. They provided opportunities to acquire education to the underprivileged and the marginalised sections, who were denied learning opportunities in the traditional education system. However only a very small fraction converted to Christianity. But the challenge posed by Christianity led to various social and religious reform movements.

Social and Religious Reforms

The English educated intelligentsia felt the need for reforming the society before involving the people in any political programmes. The reform movements of nineteenth century are categorised as 1. Reformist movements such as the Brahmo Samaj founded by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, the Prarthana Samaj, founded by Dr Atmaram Pandurang and the Aligarh Movement, represented by Syed Ahmad Khan; 2. Revivalist movements such as the Arya Samaj, the Ramakrishna Mission and the Deoband Movement. 3. There were social movements led by Jyotiba Phule in Pune, Narayana Guru and Ayyankali in Kerala and Ramalinga Adigal, Vaikunda Swamigal and later Iyothee Thassar in Tamilnadu. All these reformers and their contributions have been dealt with comprehensively in the XI Std. text book.

The reformers of nineteenth century responded to the challenge posed by Western Enlightenment knowledge based on reason. Indian national consciousness emerged as a result of the rethinking triggered by these reforms. The Brahmo Samaj was founded by Ram Mohan Roy in 1828. Other socio-cultural organisations like the Prarthana Samaj (1867), the Arya Samaj (1875) were founded subsequently. Roy’s initiative was followed up by reformers like Keshav Chandra Sen and Iswar Chandra Vidyasagar. Abolition of sati and child marriage and widow remarriage became the main concerns for these reformers. The Aligarh movement played a similar role among the Muslims. Slowly, organisations and associations of political nature came up in different parts of British India to vent the grievances of the people.

Other Decisive Factors for the Rise of Nationalism

a) Memories of 1857

Indian national movement dates its birth from the 1857 uprising. The outrages committed by the British army after putting down the revolt remained “un-avenged”. Even the court-martial law and formalities were not observed. Officers who sat on the court martial swore that they would hang their prisoners, guilty or innocent and, if any dared to raise his voice against such indiscriminate vengeance, he was silenced by his angry colleagues. Persons condemned to death after the mockery of a trial were often tortured by soldiers before their execution, while the officers looked on approvingly. It is worth recalling what Elphinstone, Governor of Bombay Presidency, wrote to Sir John Lawrence, future Viceroy of India (1864) about the British siege of Delhi during June-September, 1857: ‘…A wholesale vengeance is being taken without distinction of friend or foe. As regards the looting, we have indeed surpassed Nadirshah.’

(b) Racial Discrimination

The English followed a policy of racial discrimination. The systematic exclusion of the Indians from higher official positions came to be looked upon as an anti-Indian policy measure and the resultant discontent of the Indian upper classes led the Indians to revolt against the British rule. When civil service examinations were introduced the age limit was fixed at twenty one. When Indians were making it, with a view to debarring the Indians from entering the civil services, the age limit was reduced to nineteen. Similarly, despite requests from Indian educated middle class to hold the civil service examinations simultaneously in India, the Imperial government refused to concede the request.

(c) Repressive as well as Exploitative Measures against Indians

Repressive regulations like Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (1870), punishing attempts to excite disaffection towards the Government, and the Vernacular Press Act (1878), censoring the press, evoked protest. Abolition of custom duty on cotton manufactures imported from England and levy of excise duty on cotton fabrics manufactured in India created nationwide discontent. During the viceroyalty of Ripon the Indian judges were empowered through the Ilbert Bill to try Europeans. But in the face of resistance from the Europeans the bill was amended to suit the European interests.

(d) Role of Press

The introduction of printing press in India was an event of great significance. It helped people to spread, modern ideas of self-government, democracy, civil rights and industrialisation. The press became the critic of politics. It addressed the people on several issues affecting the country. Raja Rammohan Roy’s Sambad Kaumudi (1821) in Bengali and Mirat-Ul-Akbar (1822) in Persian played a progressive role in educating the people on issues of public importance. Later on a number of nationalist and vernacular news papers came to be launched to build public opinion and they did yeomen service in fostering nationalist consciousness. Among them Amrit Bazaar Patrika, The Bombay Chronicle, The Tribune, The Indian Mirror, The Hindu and Swadesamitran were prominent.

(e) Invoking India’s glorious Past

Orientalists like William Jones, Charles Wilkins and Max Muller explored and translated religious, historical and literary texts from Sanskrit, Persian and Arabic into English and made them available to all. Influenced by the richness of Indian traditions and scholarship, many of the early nationalists made a fervent plea to revive the pristine glory of India. Aurobindo Ghose would write, ‘The mission of Nationalism, in our view, is to recover Indian thought, Indian character, Indian perceptions, Indian energy, Indian greatness and to solve the problems that perplex the world in an Indian spirit and from the Indian standpoint.’

Birth of Indian Associations

(a) Madras Native Association

One of the first attempts to organise and vent the grievances against the British came through the formation of the Madras Native Association (MNA) on 26 February 1852.

An association of landed and business classes of the Madras Presidency, they expressed their grievances against the Company’s administration in the revenue, education and judicial spheres. Gajula Lakshminarasu, who inspired the foundation of MNA, was a prominent businessman in Madras city.

The Association presented its grievances before British Parliament when it was discussing the East India Company’s rule in India before the passing of the Charter in 1853. In a petition submitted in December 1852, the MNA pointed out that the ryotwari and zamindari systems had thrown agricultural classes into deep distress. It urged the revival of the ancient village system to free the peasantry from the oppressive interference of the zamindars and the Company officials. The petition also made a complaint about the judicial system which was slow, complicated and imperfect. It pointed out that the appointment of judges without assessing their judicial knowledge and competence in the local languages affected the efficiency of the judiciary. The diversion of state funds to missionary schools, under the grants-in-aid system, was also objected to in the petition.

The MNA petition was discussed in the Parliament in March 1853. H. D. Seymour, Chairman of the Indian Reform Society, came to Madras in October 1853. He visited places like Guntur, Cuddalore, Tiruchirappalli, Salem and Tirunelveli. However, as the Charter Act of 1853 allowed British East India Company to continue its rule in India, the MNA organised an agitation for the transfer of British territories in India to the direct control of the Crown. MNA sent its second petition to British Parliament, signed by fourteen thousand individuals, pleading the termination of Company rule in India.

The life of MNA was short. Lakshminarasu died in 1866 and by 1881, the association ceased to exist. Though the MNA did not achieve much in terms of reforms, it was the beginning of organised effort to articulate Indian opinion. In its lifetime, the MNA operated within the boundaries of Madras Presidency. The grievances that the MNA raised through its petitions and the agitations it launched were from the point of view of the elite, particularly the landed gentry of Madras Presidency. What was lacking was a national political organisation representing every section of the society, an organisation that would raise the grievances and agitate against the colonial power for their redress. The Indian National Congress filled this void.

(b) Madras Mahajana Sabha (MMS)

After the Madras Native Association became defunct there was no such public organisation in the Madras Presidency. As many educated Indians viewed this situation with dismay, the necessity for a political organisation was felt and in May 1884 the Madras Mahajana Sabha was organised. In the inaugural meeting held on 16 May 1884 the prominent participants were: G. Subramaniam, Viraraghavachari, Ananda Charlu, Rangiah, Balaji Rao and Salem Ramaswamy. With the launch of the Indian National Congress, after the completion of the second provincial conference of Madras Mahajana Sabha, the leaders after attending the first session of the Indian National Congress (INC) in Bombay amalgamated the MMS with the INC.

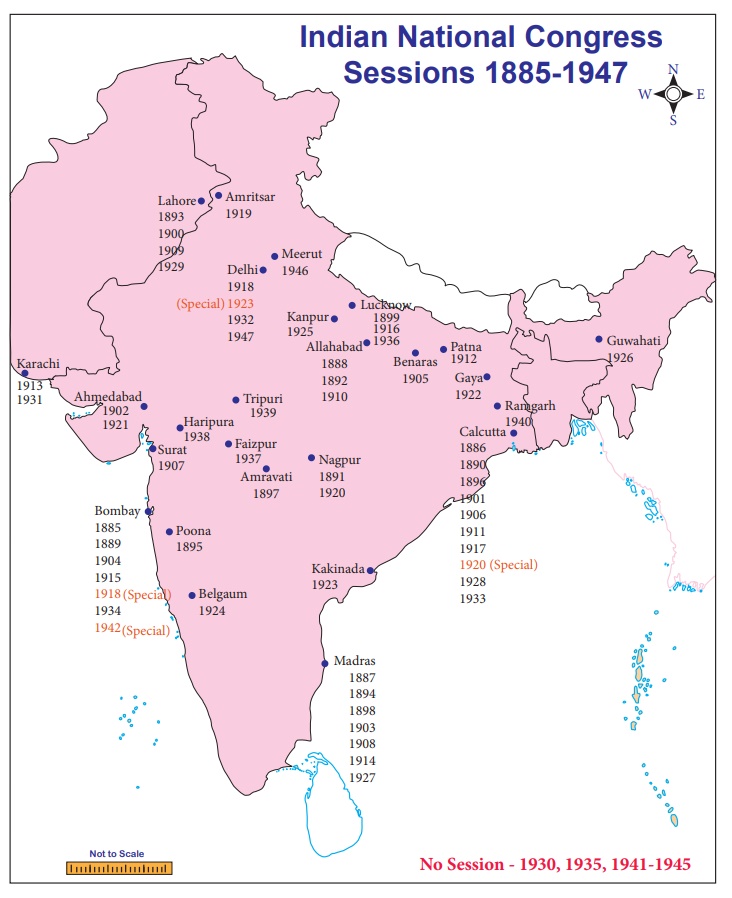

(c) Indian National Congress (INC)

The idea of forming a political organisation that would raise issues and grievances against the colonial rule did not emerge in a vacuum. Between 1875 and 1885 there were many agitations against British policies in India. The Indian textile industry was campaigning for imposition of cotton import duties in 1875. In 1877, demands for the Indianisation of Government services were made vociferously. There were protests against the Vernacular Press Act of 1878. In 1883, there was an agitation in favour of the Ilbert Bill.

But these agitations and protests were sporadic and not coordinated. There was a strong realisation that these protests would not impact on the policy makers unless a national political organisation was formed. From this realisation was born the Indian National Congress. The concept of India as a nation was reflected in the name of the organisation. It also introduced the concept of nationalism.

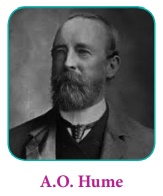

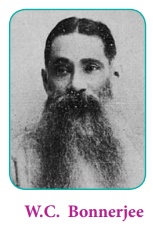

In December 1884, Allan Octavian Hume, a retired English ICS officer, presided over a meeting of the Theosophical Society in Madras. The formation of a political organisation that would work on an all India basis was discussed and the idea of forming the Indian National Congress emerged in this meeting. The Indian National Congress was formed on 28 December 1885 in Bombay. Apart from A.O Hume, another important founding member was W C. Bonnerjee, who was elected the first president.

Though the activities of the INC then revolved around petitions and memoranda, from the very beginning the founders of the INC worked to bring every section of the society into its ambit. One of the main missions of the INC was to weld the Indians into a nation. They were convinced that the struggle against the colonial rule will be successful only if Indians saw themselves as the members of a nation. To achieve this, the INC acted as a common political platform for all the movements that were being organised in different parts of the country. The INC provided the space where the political workers from different parts of the country could gather and conduct their political activities under its banner. Even though the organization was small with less than a hundred members, it had an all-India character with representation from all regions of India. It was the beginning of the mobilisation of people on an all-India basis.

The major objectives and demands of INC were

Constitutional

Opportunity for participation in the government was one of the major demands of the Indian National Congress. It demanded Indian representation in the government.

Economic

High land revenue was one of the major factors that contributed to the oppression of the peasants. It demanded reduction in the land revenue and protection of peasants against exploitation of the zamindars. The Congress also advocated the imposition of heavy tax on the imported goods for the benefit of swadeshi goods.

Administrative

Higher officials who had responsibility of administration in India were selected through civil services examinations conducted in Britain. This meant that educated Indians who could not afford to go to London had no opportunity to get high administrative jobs. Therefore, Indianisation of services through simultaneous Indian Civil Services Examinations in England and India was a major demand of the Congress.

Judicial

Because of the partial treatment against the Indian political activists by English judges it demanded the complete separation of the Executive and the Judiciary.

(d) Contributions of Early Nationalists (1885–1915)

The early nationalists in the INC came from the elite sections of the society. Lawyers, college and university teachers, doctors, journalists and such others represented the Congress. However, they came from different regions of the country and this made INC a truly a national political organisation. These leaders of the INC adopted the constitutional methods of presenting petitions, prayers and memorandums and thereby earned the moniker of “Moderates”. It was also the time some sort of an understanding about colonialism was evolving in India. There was no ready-made anti-colonial understanding available for reference in the late nineteenth century when the INC was formed. It was the early nationalists who helped the formulation of the idea of we as a nation. They were developing the indigenous anti-colonial ideology and a strategy on their own which helped future mass leaders like M. K Gandhi.

From the late 1890s there were growing differences within the INC. Leaders like Bipin Chandra Pal, Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Lala Lajpat Rai were advocating radical approaches instead of merely writing petitions, prayers and memorandums. These advocates of radical methods came to be called the “extremists” as against those who were identified as moderates. Their objective became clear in 1897 when Tilak raised the clarion call “Swaraj is my birth right and I shall have it”. Tilak and his militant followers were now requesting Swaraj instead of economic or administrative reforms that the moderates were requesting through their petitions and prayers.

Though they criticised each other, it would be wrong to place them in the opposing poles. Both moderates and militants, with their own methods, were significant elements of the larger Indian nationalist movement. In fact, they contributed towards the making of the swadeshi movement. The partition of Bengal in 1905, by the colonial government, which you will be studying in the next lesson, was vehemently opposed by the Indians. The swadeshi movement of 1905, directly opposed the British rule and encouraged the ideas of swadeshi enterprise, national education, self-help and use of Indian languages. The method of mass mobilisation and boycott of British goods and institutions suggested by the radicals was also accepted by the Moderates.

Both the Moderates and the Radicalswere of the same view when it came to accepting the fact that they needed to fulfil the role of educators. They tried to instil nationalist consciousness through various means including the press. When the INC was founded in 1885, one-third of the members were journalists. Most stalwarts of the early freedom movement were involved in journalism. Dadabhai Naoroji founded and edited two journals called Voice of India and RastGoftar. Surendranath Banerjea edited the newspaper called Bengalee. Bal Gangadhar Tilak edited Kesari and Mahratta. This is the means that they used to educate the common people about the colonial oppression and spread nationalist ideas. News regarding the initiatives taken by the INC were taken to the masses through these newspapers. For the first time, in the history of India, the press was used to generate public opinion against the oppressive policies and acts of the colonial government.

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was a firm believer that the lower middle classes, peasants, artisans and workers could play a very important role in the national movement, He used his newspapers to articulate the discontent among this section of the people against the oppressive colonial rule. He called for national resistance against imperial British rule in India. On 27 July 1897, Tilak was arrested and charged under Section 124 A of the Indian Penal Code. Civil liberty, particularly in the form of freedom of expression and press became the significant part of Indian freedom struggle.

Naoroji and his Drain Theory

Dadabhai Naoroji, known as the ‘Grand Old Man of Indian Nationalism’, was a prominent early nationalist. He was elected to the Bombay Municipal Corporation and Town Council during the 1870s. Elected to the British Parliament in 1892, he founded the India Society (1865) and the East India Association (1866) in London. He was elected thrice as the President of the INC.

His major contribution to the Indian nationalist movement was his book Poverty and Un-British Rule of the British in India (1901). In this book, he put forward the concept of ‘drain of wealth’. He stated that in any country the tax raised would have been spent for the wellbeing of the people of that country. But in British India, taxes collected in India were spent for the welfare of England. Naoroji argued that India had exported an average of 13 million pounds worth of goods to Britain each year from 1835 to 1872 with no corresponding return. The goods were in lieu of payments for profits to Company shareholders living in Britain, guaranteed interest to investors in railways, pensions to retired officials and generals, interest for the money borrowed from England to meet war expenses for the British conquest of territories in India as well as outside India. All these, going in the name of Home Charges, Naoroji asserted, made up a loss of 30 million pounds a year.