Introduction

Several events that preceded the First World War had a bearing on Indian nationalist politics. In 1905 Japan had defeated Russia. In 1908 the Young Turks and in 1911 the Chinese nationalists, using Western methods and ideas, had overthrown their governments. Along with the First World War these events provide the background to Indian nationalism during 1916 and 1920.

Europe was the main theatre of the War, though fighting took place in others parts of the world as well. The British recruited a vast contingent of Indians to serve in Europe, Africa and West Asia. After the War, the soldiers came back with new ideas which had an impact on the Indian society. India had to cough up around 367 million, of which £ 229 million as direct cash and the rest through loans to offset the war expenses. India also sent war materials to the value £ 250 million. This caused enormous economic distress, triggering discontent amongst Indians.

The nationalist politics was in low key, since the Indian National Congress had split into moderates and extremists, while the Muslim league supported British interests in war. In 1916 “the extremists” led by Tilak had gained control of Congress. This led to the rise of Home Rule Movement in India under the leadership of Dr Annie Besant in South India and Tilak in Western India. The Congress was reunited during the war. The strength of Indian nationalism was increased by the agreement signed between Hindus and Muslims, known as the Lucknow Pact, in 1916.

During the War, western revolutionary ideas were influencing the radical nationalists and so the British tried to suppress the national movement by passing repressive acts. Of all the repressive acts, the most draconic was the Rowlatt Act. This act was strongly criticized by the Indian leaders and they organised meetings to protest against the act. The international events too had its impact on India, such as the revolution in Russia. The defeat of Turkey in World War I and the severe terms of the Treaty of Sevres signed thereafter undermined the position of Sultan of Turkey as Khalifa. Out of the resentment was born the Khilafat Movement.

India and Indians had taken an active part in the War believing that Britain would reward India’s loyalty. But only disappointment was in store. Thus the War had multiple effects on Indian society, economy and polity. In this lesson we discuss the role played by Home Rule League, factors leading to the signing of Lucknow Pact and its provisions, the repressive measures of the British culminating in Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, the Khilafat Movement and the rise of an organized labour movement.

All India Home Rule League

We may recall that many foreigners such as A.O. Hume had played a pivotal role in our freedom movement in the early stages. Dr Annie Besant played a similar role in the early part of the twentieth century. Besant was Irish by birth and had been active in the Irish home rule, fabian socialist and birth control movements while in Britain. She joined the Theosophical Society, and came to India in 1893. She founded the Central Hindu College in Benaras (later upgraded as Benaras Hindu University by Pandit Madan Mohan Malaviya in 1916). With the death of H. S. Olcott in 1907, Besant succeeded him as the international president of the Theosophical Society. She was actively spreading the theosophical ideas from its headquarters, Adyar in Chennai, and gained the support of a number of educated followers such as Jamnadas Dwarkadas, George Arundale, Shankerlal Banker, Indulal Yagnik, C.P. Ramaswamy and B.P. Wadia.

In 1914 was when Britain announced its entry in First World War, it was claimed that it fighting for freedom and democracy. Indian leaders believed and supported the British war efforts. Soon they were disillusioned as there was no change in the British attitude towards India. Moreover, split into moderate and extremist wings, the Indian National Congress was not strong enough to press for further political reforms towards self-rule. The Muslim League was looked upon suspiciously by the British once the Sultan of Turkey entered the War supporting the Central powers.

It was in this backdrop that Besant entered into Indian Politics. She started a weekly The Commonweal in 1914. The weekly focused on religious liberty, national education, social and political reforms. She published a book How India Wrought for Freedom in 1915. In this book she asserted that the beginnings of national consciousness are deeply embedded in its ancient past.

She gave the call, ‘The moment of England’s difficulty is the moment of India’s opportunity’ and wanted Indian leaders to press for reforms. She toured England and made many speeches in the cause of India’s freedom. She also tried to form an Indian party in the Parliament but was unsuccessful. Her visit, however, aroused sympathy for India. On her return, she started a daily newspaper New India on July 14, 1915. She revealed her concept of self-rule in a speech at Bombay: “I mean by self-government that the country shall have a government by councils, elected by the people, and responsible to the House”. She organized public meetings and conferences to spread the idea and demanded that India be granted self-government on the lines of the White colonies after the War.

On September 28, 1915, Besant made a formal declaration that she would start the Home Rule League Movement for India with objectives on the lines of the Irish Home Rule League. The moderates did not like the idea of establishing another separate organisation. She too realised that the sanction of the Congress party was necessary for her movement to be successful.

In December 1915 due to the efforts of Tilak and Besant, the Bombay session of Congress suitably altered the constitution of the Congress party to admit the members from the extremist section. In the session she insisted on the Congress taking up the Home Rule League programme before September 1916, failing which she would organize the Home Rule League on her own.

In 1916, two Home Rule Movements were launched in the country: one under Tilak and the other under Besant with their spheres of activity well demarcated. The twin objectives of the Home Rule League were the establishment of Home Rule for India in British Empire and arousing in the Indian masses a sense of pride for the Motherland.

(a) Tilak Home Rule League

Tilak Home Rule League was set up at the Bombay Provincial conference held at Belgaum in April 1916. It League was to work in Maharashtra (including Bombay city), Karnataka, the Central Provinces and Berar. Tilak’s League was organised into six branches and Annie Besant’s League was given the rest of India.

Home Rule: It refers to a self-government granted by a central or regional government to its dependent political units on condition that their people should remain politically loyal to it. This was a common feature in the ancient Roman Empire and the modern British Empire. In Ireland the Home Rule Movement gathered force in the 1880s and a system of Home Rule was established by the Government of Ireland Act (1920) in six counties of Northern Ireland and later by the Anglo-Irish Treaty (1921) in the remaining 26 counties in the south.

Tilak popularised the demand for Home Rule through his lectures. The popularity of his League was confined to Maharashtra and Karnataka but claimed a membership of 14,000 in April 1917 and 32,000 by early 1918. On 23 July 1916 on his 60th birthday Tilak was arrested for propagating the idea of Home Rule.

(b) Besant’s Home Rule League

Finding no signs from the Congress, Besant herself inaugurated the Home Rule League at Madras in September 1916. Its branches were established at Kanpur, Allahabad, Benaras, Mathura, Calicut and Ahmednagar. She made an extensive tour and spread the idea of Home Rule. She declared that “the price of India’s loyalty is India’s Freedom”. Moderate congressmen who were dissatisfied with the inactivity of the Congress joined the Home Rule League. The popularity of the League can be gauged from the fact that Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, B. Chakravarti, Jitendralal Banerji, Satyamurti and Khaliquzzaman were taking up the membership of the League.

As Besant’s Home Rule Movement became very popular in Madras, the Government of Madras decided to suppress it. Students were barred from attending its meetings. In June 1917 Besant and her associates, B.P. Wadia and George Arundale were interred in Ootacamund. The government’s repression strengthened the supporters, and with renewed determination they began to resist. To support Besant, Sir S. Subramaniam renounced his knighthood. Many leaders like Madan Mohan Malaviya, and Surendranath Banerjea who had earlier stayed away from the movement enlisted themselves. At the AICC meeting convened on 28 July 1917 Tilak advocated the use of civil disobedience if they were not released. Jamnadas Dwarkadas and Shankerlal Banker, on the orders of Gandhi, collected one thousand signatures willing to defy the interment orders and march to Besant’s place of detention. Due to the growing resistance the interned nationalists were released.

On 20 August 1917 the new Secretary of State Montagu announced that ‘self-governing institutions and responsible government‘ was the goal of the British rule in India. Almost overnight this statement converted Besant into a near-loyalist. In September 1917, when she was released, she was elected the President of Calcutta session of the Indian National Congress in 1917.

- Dec, 1915 – Bombay INC

- 1916 – Lucknow INC President – Ambika Charan Mazumdar

- 1917 – Calcutta, INC President – Annie Besant

(c) Importance of the Home Rule Movement

The Home Rule Leagues prepared the ground for mass mobilization paving the way for the launch of Gandhi’s satyagraha movements. Many of the early Gandhian satyagrahis had been members of the Home Rule Leagues. They used the organisational networks created by the Leagues to spread the Gandhian method of agitation. Home Rule League was the first Indian political movement to cut across sectarian lines and have members from the Congress, League, Theosophist and the Laborites.

(d) Decline of Home Rule Movement

Home Rule Movement declined after Besant accepted the proposed Montagu– Chelmsford Reforms and Tilak went to Britain in September 1918 to pursue the libel case that he had filed against Valentine Chirol, the author of Indian Unrest.

The Indian Home Rule League was renamed the Commonwealth of India League and used to lobby British MPs in support of self-government for India within the empire, or dominion status along the lines of Canada and Australia. It was transformed by V.K. Krishna Menon into the India League in 1929.

Impact of the War

During the years prior to First World War the political condition of the India was in disarray. In order to win over the “Moderates” and the Muslim League with a view to isolating the “Extremists” the British passed the Minto– Morley Reforms in 1909. The Moderates observed a policy of wait and watch. The Muslim League welcomed the separate electorate accorded to them. In 1913 a new group of leaders joined the League. The most prominent among them was Muhammad Ali Jinnah who was already a member of the Congress and demanded more reforms for the Muslims.

The First World War provided the objective conditions for the revolutionary activity in India. The revolutionaries wanted to make use of Britain’s difficulty during the War to their advantage. The Ghadar Movement was one of its outcomes.

The First World War had a major impact on the freedom movement. Initially, the British didn’t care for Indian support. Once the war theatre moved to West Asia and Africa the British were forced to look for Indian support. In this context Indian leaders decided to put pressure on the British Government for reforms. The Congress and Muslim League had their annual session at Bombay in 1915 and spoke on similar tones. In October 1916, the Hindu and Muslim elected members of the Imperial Legislative Council addressed a memorandum to the Viceroy on the post-War reforms. The British Government was unmoved. The Congress and the League met at Calcutta in November 1916 and deliberated on the memorandum. It also agreed on the composition of the legislatures and the number of representation to be allowed to the two communities in the post-War reforms.

Parallel to this, Tilak and Besant were advocating Home Rule. Due to their efforts the Bombay session accepted to take back the extremist section and, consequently, the constitution of the Congress was altered. 1916 was therefore a historic year since the Congress, Muslim League and the Home Rule League held their annual sessions at Lucknow. Ambika Charan Mazumdar, Congress president welcomed the extremists: “… after ten years of painful separation… Indian National Party have come to realize the fact that united they stand, but divided they fall, and brothers have at last met brothers…” The Congress got its old vigour with extremists back into it.

Besant and Tilak also played an important role in bringing the Congress and the Muslim League together under what is popularly known as the Congress–League Pact or the Lucknow Pact. Jinnah played a pivotal role during the Pact. The agreements accepted at Calcutta in November 1916 were confirmed by the annual sessions of the Congress and the League in December 1916 at Lucknow.

Lala Hardayal, who settled in San Francisco, founded Pacific Coast Hindustan Association in 1913, with Sohan Singh Bhakna as Lala Hardayal its president. This organization was popularly called Ghadar Party. (‘Ghadar’ means rebellion in Urdu.) The members of this party were largely immigrant Sikhs of US and Canada. The party published a journal, Ghadar. It began publication from San Francisco on November 1, 1913. Later it was published in Urdu, Punjabi, Hindi and other languages.

The Ghadar Movement was an important episode in India’s freedom struggle. A ship named Komagatamaru, filled with Indian immigrants was turned back from Canada. As the ship returned to India several of its passengers were killed or arrested in a clash with the British police. This incident left a deep mark on the Indian nationalist movement.

Provisions of the Lucknow Pact

i) Provinces should be freed as much as possible from Central control in administration and finance.

ii) Four-fifths of the Central and Provincial Legislative Councils should be elected, and one-fifth nominated.

iii) Four-fifths of the provincial and central legislatures were to be elected on as broad a franchise as possible.

iv) Half the executive council members, including those of the central executive council were to be Indians elected by the councils themselves.

v) The Congress also agreed to separate electorates for Muslims in provincial council elections and for preferences in their favour (beyond the proportions indicated by population) in all provinces except the Punjab and Bengal, where some ground was given to the Hindu and Sikh minorities. This pact paved the way for Hindu–Muslim cooperation in the Khilafat Movement and Gandhi’s Non–Cooperation Movement.

vi) The Governments, Central and Provincial, should be bound to act in accordance with resolutions passed by their Legislative Councils unless they were vetoed by the Governor-General or Governors–in– Council and, in that event, if the resolution was passed again after an interval of not less than one year, it should be put into effect.

vii) The relations of the Secretary of State with the Government of India should be similar to those of the Colonial Secretary with the Governments of the Dominions, and India should have an equal status with that of the Dominions in any body concerned with imperial affairs.

The Lucknow Pact paved the way for Hindu-Muslim Unity. Sarojini Ammaiyar called Jinnah, the chief architect of the Lucknow Pact, “the Ambassador of Hindu–Muslim Unity”.

The Lucknow Pact proved that the educated class both from the Congress and the League could work together with a common goal. This unity reached its climax during the Khilafat and the Non-Cooperation Movements.

Repressive Measures of the Colonial State

Parallel to the Congress there emerged revolutionary groups who attempted to overthrow away the British government through violence methods. The revolutionary movements constituted an important landmark in India’s freedom struggle. It began in the end of the nineteenth century and gained its momentum from the time of the partition of Bengal. The revolutionaries were the first to demand complete freedom. Maharashtra, Bengal, Punjab were the major centers of revolutionary activity. For a brief while Madras presidency was also an active ground of the revolutionary activity.

In order to crush the growing nationalist movement, the government adopted many measures. Lord Curzon created the Criminal Intelligence Department (CID) in 1903 to secretly collect information on the activities of nationalists. The Newspapers (Incitement to Offences) Act (1908) and the Explosives Substances Act (1908), and shortly thereafter the Indian Press Act (1910), and the Prevention of Seditious Meetings Act (1911) were passed. The British suspected that some Indian nationalists were in contact with revolutionaries abroad. So the Foreigners Ordinance was promulgated in 1914 which restricted the entry of foreigners. A majority of these legislations were passed in order to break the base of the revolutionary movements. The colonial state also resorted to banning meetings, printing and circulation of seditious materials for propaganda, and by detaining the suspects.

The Defence of India Act, 1915

Also referred to as the Defence of India Regulations Act, it was an emergency criminal law enacted with the intention of curtailing the nationalist and revolutionary activities during the First World War. The Act allowed suspects to be tried by special tribunals each consisting of three Commissioners appointed by the Local Government. The act empowered the tribunal to inflict sentences of death, transportation for life, and imprisonment of up to ten years for the violation of rules or orders framed under the act. The trail was to be in camera and the decisions were not subject to appeal. The act was later applied during the First Lahore Conspiracy trial. This Act, after the end of First World War, formed the basis of the Rowlatt Act.

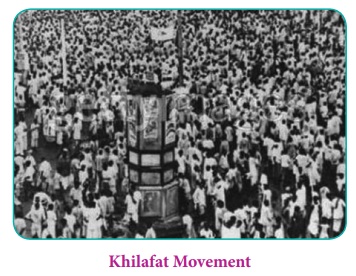

Khilafat Movement

In the First World War the Sultan of Turkey sided with the Triple Alliance against the allied powers and attacked Russia. The Sultan was also the Caliph and was the custodian of the Islamic sacred places. After the war, Britain decided to weaken the position of Turkey and the Treaty of Sevres was signed. The eastern part of the Turkish Empire such as Syria and Lebanon were mandated to France, while Palestine and Jordan became British protectorates. Thus the allied powers decided to end the caliphate.

The dismemberment of the Caliphate was seen as a blow to Islam. Muslims around the world, sympathetic to the cause of the Caliph, decided to oppose the move. Muslims in India also organised themselves under the leadership of the Ali brothers – Maulana Muhammad Ali and Maulana Shaukat Ali started a movement known as Khilafat Movement. The aim was to the support the Ottoman Empire and protest against the British rule in India. Numerous Muslim leaders such as Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, M.A. Ansari, Sheikh Shaukat Ali Siddiqui and Syed Ataullah Shah Bukhari joined the movement.

Gandhi had been honoured with Kaisari-Hind gold medal for his humanitarian work in South Africa. He had also received the Zulu War silver medal for his services as an officer of the Indian volunteer ambulance corps in 1906 and Boer War silver medal for his services as assistant superintendent of the Indian volunteer stretcher-bearer corps during Boer War of 1899–1900. When Gandhi launched the scheme of non-cooperation in connection with Khilafat Movement, he returned all the medals saying, ‘…events that have happened during the past one month have confirmed in me the opinion that the Imperial Government have acted in the Khilafat matter in an unscrupulous, criminal and unjust manner and have been moving from wrong to wrong in order to defend their immorality. I can retain neither respect nor affection for such a government.’

The demands of the Khilafat Movement were presented by Mohammad Ali to the diplomats in Paris in March 1920. They were:

1. The Sultan of Turkey’s position of Caliph should not be disturbed.

2. The Muslim sacred places must be handed over to the Sultan and should be controlled by him.

3. The Sultan must be left with sufficient territory to enable him to defend the Islamic faith and

4. The Jazirat-ul-Arab (Arabia, Syria, Iraq, Palestine) must remain under his sovereignty.

The demands of the movement had nothing do to with India but the question of Caliph was used as a symbol by the Khilafat leaders to unite the Indian Muslim community who were divided along regional, linguistic, class and sectarian lines. In Gail Minault’s words: “A pan-Islamic symbol opened the way to pan-Indian Islamic political mobilization.” It was anti-British, which inspired Gandhi to support this cause in a bid to bring the Muslims into the mainstream of Indian nationalism. Gandhi also saw this as an opportunity to strengthen Hindu–Muslim unity.

The Khilafat issue was interpreted differently by different sections. Lower-class Muslims in U.P. interpreted the Urdu word khilaf (against) and used it as a symbol of general revolt against authority, while the Mappillais of Malabar converted it into a banner of anti-landlord revolt.

Rise of Labour Movement

Introduction of machinery, new methodsofproduction, concentration of factories in certain big cities gave birth to a new class of wage earners called factory workers. In India, the factory workers, mostly drawn from villages, initially remained submissive and unorganised. Many leaders like Sorabjee Shapoorji and N.M. Lokhanday of Bombay and Sasipada Banerjee of Bengal raised their voice for protecting the interests of the industrial labourers.

In the aftermath of Swadeshi Movement (1905) Indian industries began to thrive. During the War the British encouraged Indian industries which manufactured war time goods. As the war progressed they wanted more goods so more workers were recruited. Once the war ended workers were laid off and production cut down. Further prices increased dramatically in the post-War situation. India was also in the grip of a world-wide epidemic of influenza. In response labourers began to organize to fight and trade unions were formed to protect the interests of the workers.

The success of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 also had its effect on Indian labour. A wave of ideas of class consciousness and enlightenment swept the world of Indian labours. The Indian soldiers who had fought in Europe brought the news of good labour conditions. The industrial unrest that grew up as a result of grave economic difficulties created by War, and the widening gulf between the employers and the employees, and the establishment of International Labour Organisation of the League of Nations brought mass awakening among the labours.

Madras played a pivotal role in the history of labour movement of India. The first trade union in the modern sense, the Madras Labour Union, was formed in 1918 by B.P. Wadia. The union was formed mainly due to the ill-treatment of Indianworker in the Buckingham and Carnatic Mills, Perambur. Theworking conditions was poor. Short interval for mid-day meal, frequent assaults on workers by the European assistants and inadequate wages led to the formation of this union. This union adopted collective bargaining and used trade unionism as a weapon for class struggle.

This wave spread to other parts of India and many unions were formed at this time such as the Indian Seamen’s Union both at Calcutta and Bombay, the Punjab Press Employers Association, the G.I.P. Railway Workers Union Bombay, M.S.M. Railwaymen’s Union, Union of the Postmen and Port Trust Employees Union at Bombay and Calcutta, the Jamshedpur Labour Association, the Indian Colliery Employees Association of Jharia and the Unions of employees of various railways. To suppress the labour movement the Government, with the help of the capitalists, tried by all means to subdue the labourers. They imprisoned strikers, burnt their houses, and fined the unions, but the labourers were determined in their demands.

Nationalist leaders and intellectuals were moved by the plight of the workers, and many of them worked towards organizing them into unions. Their involvement also led to the politicization of the working class, and added to the strength of the freedom movement as most of the mills were owned by Europeans who were supported by the government.

On 30 October 1920, representatives of 64 trade unions, with a membership of 140,854, met in Bombay and established the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC) under the Chairmanship of Lala Lajpat Rai. It was supported by national leaders like Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal Nehru, C.R. Das, Vallabhbhai Patel, Subhash Chandra Bose and others from the Indian National Congress.

The trade unions slowly involved themselves in the national movement. In April 1919 after the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre and Gandhi’s arrest, the working class in Ahmedabad and other parts of Gujarat resorted to strikes, agitations and demonstrations. Trade unions were not recognised by the capitalists or the government in the beginning. But the unity of the workers and the strength of their movement forced the both to recognise them. From 1919–20 the number of registered trade unions increased from 107 to 1833 in 1946–47.